… but this seems to be my destiny in this life.

(what follows is the reading I did at Richard Hull’s High Energy Amateur Science (HEAS) gathering in Richmond, VA on October 7, 2023. If you don’t care to read the whole thing, here’s an audio recording I made with my iPhone (no promises re: the quality). Photo above by David Rosignoli.

______________

Tonight’s reading is in two parts.

Part 1 is the Foreword to the 2023 Edition of The Boy Who Invented Television:

“It’s an odd mission… but this seems to be my destiny in this life.”

I tossed that line off to a friend in March 2023.

At the time I was nearing the release of my second book, The Man Who Mastered Gravity – the biography of a mercurial figure named Thomas Townsend Brown. That book is now available from booksellers worldwide.

Some guys fly to the moon. Some guys start a company and make a billion bucks. Some guys become doctors or lawyers – that’s what my parents always expected of me. Some guys become auto mechanics, bakers, candlestick makers or Indian chiefs.

Some guys become writers and publish dozens of books.

And some guys… well, so far I’ve written/published two books.

It has only taken me fifty years.

Nobody is ever going to accuse me of being prolific.

At this point…

…with far more of my life behind me than ahead – maybe the most I can hope for is having forged and hung onto my own vision of what this universe of magical things offers us here on Earth.

I believe that vision is the thread that ties these two books together, and justifies the time and effort it has taken to put them both in the world at this time.

The earliest iteration of the The Boy Who Invented Television traces back to research I started in the stacks of the UCLA Library in 1975. At the time, I was living and working on the fringes of the film and TV industry in Hollywood, and harbored aspirations of producing ‘a movie for television about the boy who invented it’ (“movies for television” were a thing in the seventies).

In the summer of 1975, I flew from LA to Salt Lake City to meet the widow and two sons of Philo T. Farnsworth, who had died four years earlier at the age of just 64. Almost fifty years later, television – the most powerful story-telling medium ever invented – has yet to explore the story of its own unlikely origins. Go figger.

Had I known then what an obsession I’d embarked on, perhaps I would have taken a different course. Bartender, maybe?

When I met her in 1975, Pem Farnsworth was beginning work on a memoir / biography of her late husband that was not published until 1990. She and her heirs granted me the rights to make that movie, but insisted on reserving the rights for a book to herself.

I researched the stories they told me. With material I found in those stacks at UCLA I corroborated their version of events and the titanic struggle between an individual genius and a monolithic corproation that left one of the most notable scientists of the 1930s in total obscurity by the 1970s.

I published a treatment of the story in an obscure periodical in 1977, in observance of the fiftieth anniversary of the first successful electronic video transmission on September 7, 1927. I helped Pem finish her book in 1989. But I did not have an opportunity publish a book of my own until 2002 – in time to coincide with the seventy-fifth anniversary.

Now What?

With one book to my credit, I embarked on my new career, as a ‘biographer of obscure 20th century scientists.’

The only question was… what obscure 20th century scientist would I write about next?

That question was answered when an anonymous email showed up in my inbox in July 2002, just a few weeks before The Boy Who Invented Television was set loose in the world. Here is where I first heard the name T. Townsend Brown. That anonymous email said…

T. Townsend Brown was another inventor who is forgotten and swept under the rug.

Science in the late 50s said what he did was against physical law, yet the government classified his work. A bunch of government contractors both American and foreign have been working on it ever since.

So where did all the R&D go? If you go out in the desert about 125 miles southwest of Las Vegas at night you will see an object flying around in the distance with a bluish haze around it. That’s where it went.

Ooooookay….

Long story short, the sequel that I started writing in 2003 was released in the spring of 2023.

The Boy Who Invented Television finally had its sequel in The Man Who Mastered Gravity.

So, one book every twenty-to-twenty five years.

With two books now in circulation, people keep asking me what I’m going to write about next.

Let’s see. I’m 72 years old now, and I publish a book every 25 years.

Do the math.

Like I said… and odd mission, an unlikely destiny.

*

You see any borders?

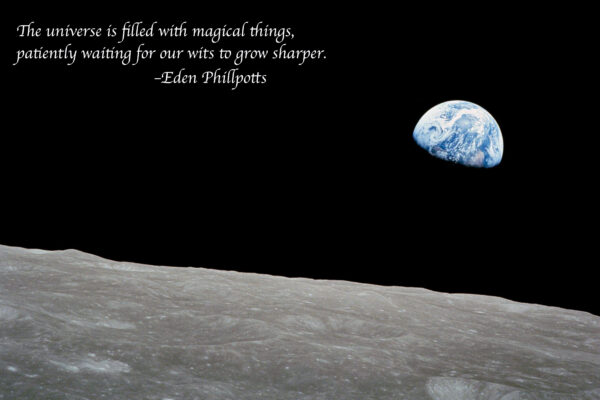

Above is what I consider to be the single most profound photograph ever taken (with the quotation that opens The Man Who Mastered Gravity).

Countless millions, probably billions and maybe trillions of photos have been taken of individual humans since the first Daguerreotypes were exposed and printed in the 19th Century.

But Earthrise is the first photo in which all of humanity was captured in a single frame – suspended in a vast cosmic void.

Philo Farnsworth was always intrigued with the possibility of traveling through that vast cosmic void. In 1926, as the newlyweds Pem and Philo rode a ferry across the San Francisco Bay under a moonless sky, he pointed toward the stars and confided his ambition to ‘go out there someday.’

That such a thing was even remotely ponderable in the 1920s is testament to the vision that Philo Farnsworth shared with the likes of Albert Einstein.

Philo Farnsworth arrived on Earth in 1906 – a year after Albert Einstein reshaped human understanding with his radical ideas about the elastic qualities of time and space and the equivalence of matter and energy. All of the work that Farnsworth did over the course of his lifetime was borne from that new cosmology.

As mundane an appliance as it sometimes seems, that cosmology cleared the path for the advent of television. You may be watching The Real Housewives of Transylvania, but that transmission is coming to you courtesy the most advanced concepts the human mind has ever pondered.

There is still a tendency in some circles to dismiss Farnsworth’s contribution to the inventing of television as just one among many. I cringe every time I read that Philo Farnsworth was just one of countless “pioneers” who made television possible. Such a reduction does a great service to the arc of human capacity and achievement.

The way I see it, Farnsworth’s first patents express a breakthrough of epic proportions.

The sketch of a television camera tube that 14-year old Philo Farnsworth drew for his high school science teacher in 1922 embodies the very first paper that Albert Einstein published in the Miracle Year of 1905. By introducing a particle theory of light, Einstein’s articulation of the photoelectric effect laid the foundation for all the quantum physics that came after it, but few today remember that that is the discovery for which Einstein won his Nobel Prize in 1921.

TV: The New Cosmology

It seems obvious now, nearly a hundred years later.

But at the time, when Farnsworth wrapped Einstein’s first discovery in a vacuum tube, he achieved a breakthrough in what humans could do to focus and steer quantum forces and particles. The Image Dissector tube rendered obsolete all the spinning wheel attempts at television that had that had preceded it and made possible everything that has come since – from ultra-high-definition, wall-sized flat-panel displays to these smartphones that fit in our pockets.

Someday, the cosmology first expressed by Albert Einstein – and embodied in Farnsworth’s ideas for electronic television – will carry mankind beyond the threshold that Bill Anders captured through the window of Apollo 8 in 1968. I suspect that some of Philo Farnsworth’s most closely held secrets will be along for that ride.

I only came to that conclusion after spending another two decades trying to make sense of the material that earlier this year finally found its way into that long-awaited sequel, The Man Who Mastered Gravity.

But the second book is not so much a ‘sequel’ as the two books together are of a single piece; together, they circle two advanced technologies that remain tantalizingly out of the reach of Earthbound humans: fusion energy and gravity control.

I don’t want to say much more about that here. You’ve got a book to read first. And then, I hope, you’ll be sufficiently intrigued to read another.

Like I said, it’s an odd destiny.

Here endeth part 1 of tonight’s reading.

*

Part 2

I have been thinking a lot lately about how, where, and when these two stories dovetail together.

I’ve only asked myself that question a jazillion times over the past twenty years. In the course of one of podcast interview back in June, I found myself – finally! – beginning to articulate the point where these two stories are in perfect congruence.

First, I will cite passage from the Townsend Brown biography, and then a synchronous story from the Philo Farnsworth bio.

We Will Just Sail Away

In The Man Who Mastered Gravity there is a marvelous scene from the spring of 1927, when Townsend Brown is courting Josephine, the young woman would become his wife. By the time he took her sailing on Ohio’s Buckeye Lake, he had found a receptive enough audience for his unorthodox ideas to be comfortable expressing one of his most cherished visions (this is an excerpt from Chapter 14):

As their little sailboat skimmed across the surface of the lake, Josephine tried to lighten the mood.

“OK, Mr. Smarty, if you could travel through time, what do you think you will find in the future? Will there be more wars? What will become of Mankind in the future?”

The young dreamer with the tiller in one hand and the mainsheet in the other knew it was time to share the vision he had seen in his dreams.

“We will just sail away,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“Someday, men will travel in space, just as easily as we are sailing now. Great ships will silently push away from the Earth just as easily as this sailboat pushed away from the dock.”

Josephine closed her eyes and tried to imagine their little boat sailing across the void of space. In her heart she knew she was hearing something not only strange and fantastic, but also true.

Remember, this is a story from the mid-1920s, roughly the time when Robert Goddard was conducting his very first experiments with the sort of rocket-propulsion that would eventually blast men into orbit and off to the moon. Rocketry was barely out of its cradle, and already Townsend Brown was dismissing it – as he would describe it in years hence – as “brute and awkward force.”

The idea that Townsend shared with Josephine demonstrates that just as necessity is the mother of invention, like wise invention is the mother of new horizons. Once you begin to see things differently, the experience that follows opens still more new possibilities in the realm of the unorthodox.

The Pineapple and The Pea

As Townsend Brown envisioned great vessels simply pushing away from the Earth, Philo Farnsworth nurtured a similar vision borne of his unique singular experience.

In the summer of 1926, Farnsworth was still a year away from delivering television into the world, but already he could sense what the future had in store. And, like Townsend Brown, he expressed that vision to his wife while they were on a boat.

Farnsworth’s laboratory was at the foot of Telegraph Hill in San Francisco; the cottage he shared with his new wife Pem was across the bay in Berkeley. They often spent their days in the lab together. Pem contributed drawings and diagrams for the patents and helped with administrative chores while Phil and Pem’s brother Cliff Gardner began fabricating tubes and circuits.

As described in Chapter 4 of The Boy Who Invented Television:

The first few months in San Francisco were a heady and romantic time for the newlywed Farnsworths. One night in particular stood out in Pem’s memory—a brisk, moonless night in January when she and Phil were taking the late ferry back to their cottage on Derby Street.

They’d walked out on the deck, and Phil pointed out some of the constellations and planets he had learned from his father. Then, out of the blue, Phil said “Some day, I’m going to build a space ship and go out there—and I hope that you will want to go with me.”

A chill ran down Pem’s spine. She’d never been off the ground, never even been up in an airplane. Now, suddenly, the man she had married, a man she knew was quite capable of achieving any fanciful dream he imagined, was proposing to take her into the infinite darkness of space.

The very thought of it scared her witless. She was silent for a full minute, until Phil asked her, “Does that scare you?”

“Yes,” Pem answered, “it scares me to death. But I’m not going to let you go off into space without me. I get goose bumps just thinking about it, but I suppose I’d rather die with you in space than live on Earth without you.”

“That’s my girl,” Phil said with a smile, “That’s what I wanted to hear. But you can relax, we’ve got a lot to do before we could take on such a project, and it may take longer than we think to make something commercial out of television.”

From the work he did over the next decade “to make something commercial out of television,” Farnsworth learned to do with quantum mechanics more than any man alive at the time.

And from his novel vacuum tubes came the inspiration for a device that could bottle a star – and from that conception came his own unique sense of what the future might have in store.

In the middle of the 20th century, as mankind challenged gravity with ever more powerful rockets, Farnsworth expressed his vision for space travel using the analogy of “a pineapple and a pea.”

With rocket propulsion, Farnsworth would say, the first Earthlings in space needed a launch vehicle “the size of a pineapple” in order to lift a payload “the size of a pea.”

Just picture the Saturn V rocket that took the Apollo astronauts to the moon: a Volkswagen-sized spacecraft sits atop a 40-story-tall fuel tank – and much of that fuel was burned just getting the rest of the fuel off the launch pad!

With fusion energy as the source of propulsion, Farnsworth believed, that ratio would be reversed: a fusion-powered launch vehicle “the size of a pea” would lift a payload “the size of a pineapple.”

A ‘fusion powered future’?

In the last chapters of The Boy Who Invented Television, Farnsworth speaks of…

…small, fusion-powered rockets gently lifting enormous payloads into orbit. Once in orbit, fusion-powered spacecraft could make it to Mars on as much nuclear fuel as could be stored in a tank the size of a fountain pen…”

This is where the two stories intersect: “…gently lifting enormous payloads…” sure sounds a lot to me like “silently pushing away from the Earth just as easily as this sailboat pushed away from the dock.”

Farnsworth may not have been thinking in terms of synthetic gravity any more than Townsend Brown was thinking of synthetic stars, but the two ideas fit together perfectly: The electrical potential of Philo Farnsworth’s fusion reactor is precisely what Townsend Brown needed to produce artificial gravity in an engine not much larger or heavier than the V8 in my Mustang.

And a vessel that can ‘just sail away’ sounds like ‘a pea propelling a pineapple’ to me.

Taken together, these two stories suggest that mankind has come so far along in his technological progress that he has reached a threshold, beyond which lies that “universe of magical things” that Eden Phillpotts speaks of in the epigraph that opens The Man Who Mastered Gravity:

And then comes the daunting question: if we have reached that threshold, why can’t we cross it?

And with that quandary, here endeth tonight’s reading.

Thank you for your time and attention.